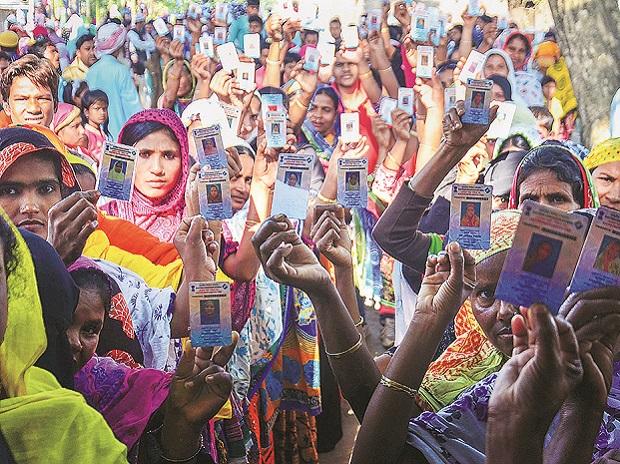

A record 65.3 per cent of India’s 260 million women voters cast a ballot in the 2014 polls that swept Modi to the biggest parliamentary majority in three decades

To see how India’s women are becoming a powerful political force ahead of next month’s election, look no further than Neelam Kumari and her bright yellow van.

The 35-year-old living in one of India’s poorest states bought the vehicle with a Rs 600,000 ($8,400) loan from a government program, allowing her to earn Rs 14,000 a month ferrying children to a nearby school. She gives the credit—and plans to give her vote—to Prime Minister Narendra Modi.

“My son and the other kids in our village wouldn’t have gone to an English school if not for this loan,” Kumari said from her dusty village in Bihar, a state that is crucial to Modi’s bid to win another five-year term. Five other women in nearby villages now own vans like hers, and they also back Modi.

Kumari is among 56.3 million rural women—equivalent to the population of Italy—who have received small loans worth about $27 billion since Modi took office in 2014. They could help swing the next election in May: Female voters are becoming an increasingly potent constituency in a nation where crimes against them regularly stir global outrage.

A record 65.3 per cent of India’s 260 million women voters cast a ballot in the 2014 polls that swept Modi to the biggest parliamentary majority in three decades. In most states, female turnout has surpassed males in recent ballots. And that is now starting to produce real change: Modi’s government has raised expenditure on sanitation and education for girls, provided safer cooking fuels and instituted the death penalty for rapists.

“In 2019, Modi sees women as an important demographic that can help power the party’s reelection,” said Milan Vaishnav, South Asia director at the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace. “The BJP believes that women will reward the party for their welfare delivery schemes.”

The loan program is called Aajeevika (it translates to livelihood), and it was started in the 1990s as a local poverty alleviation program for women’s groups in the southern state of Andhra Pradesh. It was adopted country-wide in 2011 under the Congress-led government that Modi ousted three years later.

Once in power, Modi expanded Aajeevika to 622 of India’s 640 districts and increased annual outlays by about three times. The federal government makes funds available and local governments oversee implementation—a task made relatively easier with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party and allies ruling 16 of India’s 28 states.

It works like this: Women save as little as Rs 10 (14 cents) to create a corpus before receiving a state grant. They then open bank accounts based on this savings and credit history. This allows them to apply for low-interest loans and grants to fund small businesses. Bad loans in the program are at a mere 2.6 per cent compared to 10.8 per cent in corporate bad loans.

Kumari’s home of Bihar has more participants in the program than anywhere else in India. And women in the state have shown Modi and other politicians just how women’s collectives could bring political gains.

Their most striking achievement came in 2015, when Modi’s political ally and Bihar’s chief minister Nitish Kumar banned alcohol in the state. The move came after women’s groups in the loan program complained of men who regularly drank away the family’s earnings, leaving nothing for food, housing or health care.

“We were trying to save money and repay whatever loans we took,” said Rita Devi, a homemaker from Simraoka village. “But our men spent it all on drinking.”

When Kumar visited the women’s group on a campaign stop for state elections, he asked for their vote. They told him they would if he imposed prohibition.

“The huge crowd of sisters wouldn’t stop clapping when I said that,” Devi said. “He got our message. And made us a promise.”

Kumar was reelected, and almost immediately banned alcohol sales in Bihar. As a token of gratitude, he sent a 100,000-rupee grant to Rita’s village—and she says local men in her village haven’t dared take the women lightly since. The story resonated across the country.

Outstanding loans for the women collectives now averages about $9 billion a year, government data shows. Under a separate plan called Mudra, which lends to small businesses and non-profits, 73 per cent of advances have gone to women.

“This bringing together of women has created economic networks of women like we’ve never had before,” said Nita Kejrewal, joint secretary in the Ministry of Rural Development. Cheaper interest rates on loans have helped raise risk appetite.

The networks have grown so strong that they are conduits for other government programs such as building toilets in rural communities, according to Amarjeet Sinha, an official in the Ministry of Rural Development.

Women’s groups in Aajeevika have contributed to the 90 million toilets built across rural India since 2014—taking sanitation coverage in India’s hinterland to over 98 per cent from 39 per cent. Programs to prevent malnutrition, dowry and child marriage have also been supported by women in the program.

“These may seem like merely welfare programs, but they are creating unique governance structures,” said Shaibal Gupta, economist and member secretary of the Asian Development Research Institute. “Raising earnings has helped reduce atrocities on women and, according to a study we did, it has increased trust among citizens and government.”

That’s vital for a nation that ranks in the bottom fifth among 153 countries on security and inclusion and where 20 million women have vanished from the workforce since 2004.

How effectively that trust translates into votes for Modi may well dictate the outcome of a tightening election come May. His opponents led by the Congress party didn’t respond to texts and calls seeking comment.

Even so, women in rural Bihar who have received loans under the Aajeevika are almost all in Modi’s camp.

“We will listen to our families and will discuss among ourselves,” says 36-year-old Ranju Devi, who runs a food store in rural Gaya. “Our vote will go to Modi if he promises to look after our welfare.”